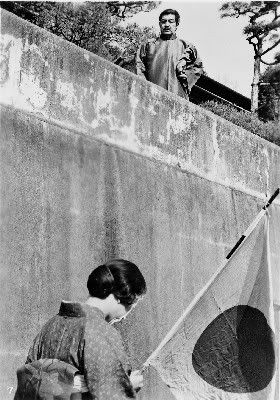

A Bloody Spear on Mt Fuji's plot is basic; a group of travellers (Samurai and two servants, shamisen player and daughter, highway policeman, thief, miner) interact and become closer through stressful and comedic situations (also, some tragedy). Ostensibly a road movie, a lot of the interaction and activity takes place in inns and city streets, very little on roads (though what does is memorable, such as Gonpachi becoming acquainted with an young orphan boy admirer, pictured above.) Most of the plot revolves around the samurai, whose character reminds one of Yamanaka taking a stand against society and paying the price. I wonder if this inference was an accident (Yamanaka made popular films that questioned the status quo in the 30s, was sent to Manchuria and died at the front shortly after; only three of his films survive today.)

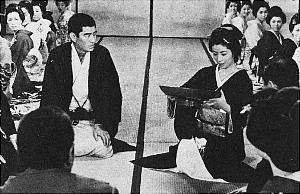

There are many great moments in the film, which is as comedic in dialogue as it is in editing and tone. Daisuke Kato plays one of the servants, and his sake drinking and philosophizing scenes are everyman humor at its best. The playful looks, dialogue, and subtle attraction between the shamisen player and Gonpachi (Chiezo Katoaka), lords sitting on a busy highway to Edo shutting down traffic for a tea ceremony, and the lancer's final battle all stick close to my memory. I can't think of any other postwar Samurai film that does this kind of action, comedy, and drama as entertainingly (my favorite postwar jidai-geki films are the Anti-Samurai ones, such as Okamoto's Sword of Doom).

If you, like me, were taken wholly by surprise while watching Yamanaka Sadao's Tange Sazen and the Million Ryo Pot then you'll greatly appreciate this film (only available as a bootleg with english subtitles here, though there are rumors this and more Yamanaka could get an North American release soon). It shares with the 1935 genre picture a sense of humor and lightheartedness that few films have done as well. In fact, since Uchida Tomu directed this jidai-geki with the help of Shimizu Hiroshi and Ozu Yasujiro, I can only imagine it's a heavy homage to their lost friends Yamanaka and Itami Mansaku. Itami's film Capricious Young Man can be felt all over, especially in it's depiction of the samurai servants mingling with each other and arguing about their duties. Ozu and Shimizu's touch can also be felt with the depiction of the child, as it's characteristically their own. He's rebellious and witty, but also retains childish attention getting ways, and lack of self restraint in all matters. Ozu and Shimizu used this type of childish antics in their films regularly to great effect (particularly in Ozu's I Was Born But... and Shimizu's Children in the Wind.)

Uchida's history is an interesting one. He went to war, and after 1940 spent ten years in a prison camp in China (more on this part of his life, and some notes by Craig Watts about Bloody Spear at Bright Lights Film Journal). He began directing silents and moved on to become one of the late thirties preeminent social realist directors, making a powerful play with Earth (1936), made almost entirely with extra film stock from other productions. His other late thirties work, Theater of Life, Police, and Unending Advance were preferred by Donald Richie and have garnered critical appreciation from critics like David Bordwell, Keiko McDonald, and midnighteye.com (any information on where to find those three films on video would be greatly appreciated by me, by the way). His samurai films from the 50s and 60s have aged relatively well, especially this and his Musashi Miyamoto pentalogy. Toei made mostly low grade cheesefests, but were known to throw in a "prestige" film every now and then, of which Bloody Spear at Mt Fuji definitely categorizes itself. With the big name writer/directors, and headlining actor Chiezo Kataoka, this was surely a success.

You can buy this film with french subtitles at Amazon France, though I found a copy with an english translation by fishing around. Also, there's a great overview of Uchida's career at Senses of Cinema by Alexander Jacoby. Also, be sure and pick up Masters of Cinema's absolutely necessary DVD of Yamanaka's Humanity and Paper Balloons. I'll hopefully get a chance to see his other acclaimed 1955 film Twilight Saloon, but first I'll have to save up some cash to get the unsubbed import.