EROS PLUS MASSACRE

Friday, December 31, 2010

R.I.P. Takamine Hideko, 1924 - 2010

Her beauty and wry smile are on FULL display as Carmen in this clip from Kinoshita Keisuke's Carmen Comes Home, from 1951, with her Shochiku approved late-occupation challenge to traditional patriarchal values.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time 時をかける少女 (Hosoda Mamoru 細田守, 2006)

Hosoda Mamoru's The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is an imaginative story about a girl who accidentally becomes able to go back in time to replay her day's events with a simple leap (its never made explicit, but it seems the harder she leaps, the further she goes back in time, but you never know.) Its basically a shojo style anime where the girl takes center stage and faces tough questions about growing up. Of course, these tough questions are given a new spin because not only can she literally avoid answering them, but change what she says once she says it. The film is so well done, however, that it never becomes even remotely obtuse and is easily followed from beginning to end.

The animation is absolutely gorgeous, combining hand drawn and digital through high tech layering software, and achieving a combined effect of realism and beauty that few cartoons can lay claim to (in this way it felt a sister film to Takahata's Only Yesterday and My Neighbors the Yamadas.) If you find yourself staring endlessly at the backgrounds, you're not alone. Nature is on full display in this film, and the characters that inhabit it never seem far from a stream or flock of birds. Sunlight glinting off of sign posts, fields saturated in pastel greens, and the cozy warmth of indoor nesting play a large part in setting the mood. Character designs are detailed but not distracting, with all the main characters having expressive unique faces that don't veer off into the Anime extremes. The sound is a huge factor in the film, as it should be in all animation in my opinion, with subtle and effective voicework.

I have a feeling this will become one of my most watched animes. It has a sense of humor about itself, but the emotional notes ring very true. You find yourself caught up in a world where reality isn't exactly what it should be, but the stakes aren't all that high in the larger universal context. What you end up with is a story about relationships, ethics, communication, and the inevitability of making mistakes.

Hosoda Mamoru was a Studio Ghibli animator and was set to direct Howl's Moving Castle, but declined and went on to work on his own projects. Howl's Moving Castle seems, in retrospect, like the last movie in the world this director should be involved with. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time reminds me more of Kondo Yoshifumi's If You Listen Closely (or Whispers of the Heart), one of my most beloved films, about a young girl also facing adulthood who lives partly in a world of fancy. For this film he's been nominated for a number of awards, and hopefully will begin work on new projects soon.

This film is available with on DVD with english subtitles in Korea.

Friday, August 03, 2007

A Bloody Spear on Mt. Fuji 血槍富士 (Uchida Tomu 内田吐夢, 1955)

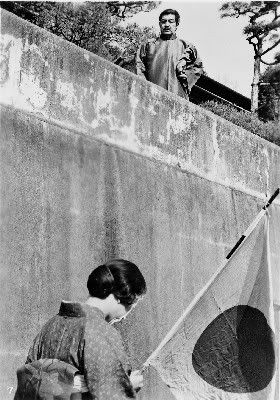

A Bloody Spear on Mt Fuji's plot is basic; a group of travellers (Samurai and two servants, shamisen player and daughter, highway policeman, thief, miner) interact and become closer through stressful and comedic situations (also, some tragedy). Ostensibly a road movie, a lot of the interaction and activity takes place in inns and city streets, very little on roads (though what does is memorable, such as Gonpachi becoming acquainted with an young orphan boy admirer, pictured above.) Most of the plot revolves around the samurai, whose character reminds one of Yamanaka taking a stand against society and paying the price. I wonder if this inference was an accident (Yamanaka made popular films that questioned the status quo in the 30s, was sent to Manchuria and died at the front shortly after; only three of his films survive today.)

There are many great moments in the film, which is as comedic in dialogue as it is in editing and tone. Daisuke Kato plays one of the servants, and his sake drinking and philosophizing scenes are everyman humor at its best. The playful looks, dialogue, and subtle attraction between the shamisen player and Gonpachi (Chiezo Katoaka), lords sitting on a busy highway to Edo shutting down traffic for a tea ceremony, and the lancer's final battle all stick close to my memory. I can't think of any other postwar Samurai film that does this kind of action, comedy, and drama as entertainingly (my favorite postwar jidai-geki films are the Anti-Samurai ones, such as Okamoto's Sword of Doom).

If you, like me, were taken wholly by surprise while watching Yamanaka Sadao's Tange Sazen and the Million Ryo Pot then you'll greatly appreciate this film (only available as a bootleg with english subtitles here, though there are rumors this and more Yamanaka could get an North American release soon). It shares with the 1935 genre picture a sense of humor and lightheartedness that few films have done as well. In fact, since Uchida Tomu directed this jidai-geki with the help of Shimizu Hiroshi and Ozu Yasujiro, I can only imagine it's a heavy homage to their lost friends Yamanaka and Itami Mansaku. Itami's film Capricious Young Man can be felt all over, especially in it's depiction of the samurai servants mingling with each other and arguing about their duties. Ozu and Shimizu's touch can also be felt with the depiction of the child, as it's characteristically their own. He's rebellious and witty, but also retains childish attention getting ways, and lack of self restraint in all matters. Ozu and Shimizu used this type of childish antics in their films regularly to great effect (particularly in Ozu's I Was Born But... and Shimizu's Children in the Wind.)

Uchida's history is an interesting one. He went to war, and after 1940 spent ten years in a prison camp in China (more on this part of his life, and some notes by Craig Watts about Bloody Spear at Bright Lights Film Journal). He began directing silents and moved on to become one of the late thirties preeminent social realist directors, making a powerful play with Earth (1936), made almost entirely with extra film stock from other productions. His other late thirties work, Theater of Life, Police, and Unending Advance were preferred by Donald Richie and have garnered critical appreciation from critics like David Bordwell, Keiko McDonald, and midnighteye.com (any information on where to find those three films on video would be greatly appreciated by me, by the way). His samurai films from the 50s and 60s have aged relatively well, especially this and his Musashi Miyamoto pentalogy. Toei made mostly low grade cheesefests, but were known to throw in a "prestige" film every now and then, of which Bloody Spear at Mt Fuji definitely categorizes itself. With the big name writer/directors, and headlining actor Chiezo Kataoka, this was surely a success.

You can buy this film with french subtitles at Amazon France, though I found a copy with an english translation by fishing around. Also, there's a great overview of Uchida's career at Senses of Cinema by Alexander Jacoby. Also, be sure and pick up Masters of Cinema's absolutely necessary DVD of Yamanaka's Humanity and Paper Balloons. I'll hopefully get a chance to see his other acclaimed 1955 film Twilight Saloon, but first I'll have to save up some cash to get the unsubbed import.

Monday, July 30, 2007

Age of Assassins 殺人狂時代 (Okamoto Kihachi 岡本喜八, 1967)

We begin with exposition as a lunatic asylum "mad scientist" ex-Nazi played by Amamoto Eisei discusses (he and his pals switch back and forth between menacing Japanese and scary German the whole film) how a massive diamond was lost and a young Japanese (Nakadai Tatsuya) has it in his possession- within his body, actually. A league of professional, and would-be, assassins make comedic attempts at Nakadai's life which are all thwarted, naturally, since even playing a little bit of a "dweeb", Nakadai is naturally graced with luck, charisma, wit, and a respectable fighting (or dodging) abilty. Turns out the diamond is a stolen Nazi item which was placed in Nakadai's body when he was eight. Nakadai is accompanied by a girl (Dan Reiko pictured above, fairly well known as Yuriko from Ozu's The End of Summer) and a goofy pal, who seems childishly eager for action.

Its telling that Okamoto's wildly hilarious, and sadly overlooked, film Age of Assassins (also known as The Epoch of Murder and Madness) shares its title, 殺人狂時代, with the Japanese translation of Charles Chaplin's blue beard Monsieur Verdoux. Both are the blackest of dry comedies, with a lack of sentimentality, light treatment of murder, and globe trotting anti-heroes making their way through piles of awkward situations and exotic, bizarre characters, both making oblique or vague swipes at politics. Chaplin plays for keeps more often than Nakadai, but Nakadai has a geeky coolness which seems to cross his dead stare from Teshigahara's Face of Another with the jaunty confidence of his character from Kill! that in some ways trumps Chaplin's foppish creepiness.

Though as much of a spoof of the spy film, with sultry femme fatales, gunplay, and strange gadgets, as a continuation of the "everyman" character Okamoto was so much a fan of, Age of Assassins manages to be fun and seemingly timeless, in a way few comedies can be. Watching this grasping even the smallest bit of dialogue is still entertaining after a handful of viewings. The same can be said of his other comedies that I've seen, including the sometimes maligned Oh, Bomb!, which is certainly among the most unique films of the 60s (something to be said for that, I believe.) It, like many dark comedies, defies categorization, and absolutely sets in stone what is commonly called the "Kihachi Spirit" in Japan, a sort of untouchable and undefinable quality Okamoto's films have, which is oh so modern.

The credits feature a DePatie-Freleng styled animated segment, which is probably the closest it comes to being dated. Concerning the visual style, Okamoto used the same cinematographer for this as Kill!, so it has a similar crisp detail, but it's a bit more high contrast (inspired by the black and white film noir underworld of assassins and spies, I suppose.) The score is almost inappropriately "emotional" at times, but enhances the odd factor. The action is believable, in a "chase film" sort of way, but the real greatness of Epoch of Murder and Madness is in the comedy. Not too broad (though Nakadai's small-enough-to-pedal-with-your-feet car, which emits burps and farts as it runs, runs counter to that claim) and like most of his films anti-authority and anti-war, a fair bit of cynicism and a love for the details of human nature seem to be the ideas behind it. A bit of his earlier The Elegant Mr. Everyman can be seen in the way Nakadai uses his voice as a blunt instrument of humor, streamlining dialogue in a way that almost sounds like narration. The cynical soldier, with aims at the ridiculousness of war, is then best exemplified in his Nikudan, or The Human Bullet, where Nakadai's Assassins character, Kikyo Shinji seems to be transposed into the Special Attack Forces. Properly enough, Nakadai narrated Human Bullet and the evil as hell Amamoto Eisei plays the main character's father (i.e. the villain). Worth noting that the "main character" of Human Bullet, played by Terada Minori, goes unnamed.

Someone needs to bring this, and the rest of Okamoto's comedic sixties work, to DVD badly. These films are so good (Oh, bomb!, The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman, and The Human Bullet), they must be seen to be believed.

Sunday, July 29, 2007

Coup d'etat 戒厳令 (Yoshida Kiju 吉田喜重, 1973)

Firstly, apologies for being so long out of touch.

Yoshida "Kiju" Yoshida (whose Eros Plus Massacre this blog is named after) directed his last film for some time in 1973. This was a strange biopic about a military obsessive and nationalist socialist named Ikki Kita, somewhat in the style of Hitler, who encouraged a coup against the Japanese government in 1936 (infamously known as the "February 26th incident".) I say strange because a number of choices were made which gave the

film a unique place in the history of biopics and specifically historical reenactments of the coup. Rarely has a biographical film been done with such a confident and dramatic touch.

Yoshida's framing is the stuff of film legend, nearly always placing figures at the edges of cinema (and therefore not altogether video friendly, before the advent of DVD that is.) It's a nearly dizzying effect handled graciously, which lends the events a larger than life feeling, that feels artistically justified instead of rammed down your throat. The black and white colors are used to their most effective ends, with entrancing expressionistic details. Textures of wood and granite play a large part in setting moods, along with a lack of establishing shots and action sequences, making this a more quiet film than anyone would expect of its reputation and name.

The music choices of Ichiyanagi Sei, who worked on a number of Yoshida films, recalls Jissouji's Mujo (or This Transient Life) which seems as interested in minor key fiddle flourishes as Takemitsu styled percussion explosions. The score also boasts a twice repeated analog keyboard motif, which shows the melancholy and absence of life among the militarists. It underscores both a reprehensibly dour dream sequence, and channels an avant funeral march before the credits roll. Watkins' Edward Munch and 32 Short Films about Glenn Gould come to mind in the use of music effectively rendering someone's life story to film.

In regards to its place among reenactments, as Joan Mellen noted in Waves at Genji's Door, most filmed versions of this story encourage a sentimentalism of the officers involved, as they were merely doing the most honorable thing they could imagine by assisting the Emperor in getting rid of the waste of civilian bureaucracy. The officers are treated with sympathy, but more for their naivete in the face of the unknown future, rather than Yoshida siding with their proto-fascists ways.

The major emotional issues in the film stem from Ikki's childhood and paternal issues towards his stepson, and how that carries over into his dealings with one of the more inept but sincere acolytes. Ikki's dealings with authority figures is flippant at best, and he seems to regard society as a mere gesture, with martial law being the only true way for humanity to progress. Yoshida's rendering of these beliefs should be held up with his even more powerful Eros Plus Massacre, where Taisho anarchism and the late 60s student movement are entangled and commenting on one another. There, Yoshida appears to be telling us something about the nature of humanity, in that it doesn't really change, but only cons one into thinking it will. In Coup d'etat, Yoshida seems to be saying not only will things remain the same, but they're usually worse than you realize.

Saturday, April 07, 2007

Battle Royale バトル・ロワイアル (Fukasaku Kinji 深作 欣二, 2000)

I've been lagging a bit in posting, for a number of reasons, but they are all extremely boring (family, work, sickness, and laziness among them.) I did manage to catch something truly bizarre and interesting out of left field the other day, a film that I had written off a few years ago without having seen it (usually a good thing), but went looking for it after having it recommended in a couple of different books: Fukasaku Kinji's Battle Royale. Fukasaku, having lived through WWII, and experienced senseless violence and innocent deaths all around him, is obviously making a political point in this still very entertaining action/adventure film. What the point exactly is, I'm not sure, but maybe a closer look will help. There will surely be spoilers here.

Battle Royale begins by showing some statistics: Japan faces %15 unemployment at the turn of the millennium, and the rebellious youth are the first scapegoats and victims of the government's reaction. It then races to a shot of various military and media figures surrounding a single, bloody, smiling girl, referred to as the "survivor". We're then in a school, and a teacher (Kitano Takeshi) is stabbed by a wild male student running through a school corridor. A female student watches in curious horror, and meets the teacher's gaze. As the film progresses, a busload of kids are drugged during their class trip, taken to a deserted island, and told that they will have to kill each other until one is left, or they will all die.

As one student after another dies at the hands of a previous friend, or foe, we see a barrage of cliches, old and new, taken to a brutal extreme. Fukasaku seems to be poking fun at some of the popular Shouju films where boys are embarrassed to talk to girls, whole plotlines revolve around whether a friend is really a friend, and rich and attractive youth walk over the modest and poor. We see double suicides, deathbed confessions, extreme loyalty, and false loyalty all play out in macabre blood splattering violence. Even in this extreme environment, with the end of their lives nigh upon them, these people cannot let go of the social constraints placed on them by tradition. But this island, much like Golding's Lord of the Flies (the film has many similarities), is also a microcosm of Fukasaku's current perception of society, greatly influenced by his war years: A government will not hesitate to sacrifice you to preserve itself.

Kitano's teacher, ostensibly in charge of the operation, seems to know this, but is so jaded and emotionless about carrying out his country's duty, that only toward the end does he falter. Whatever strange ideas possess this character remains a mystery. His obsession with the major female lead, Noriko (she seems to stand out as the most delicate and innocent of the film's female roles) also seems to lead to a dead end. Maybe more viewings will help.

But in the end, two people walk away alive, and they are wanted for murder (certainly a shot at the idea of War Crimes implicating the common soldier and letting the real criminals in charge go free in postwar Japan.) The adult world has indeed completely sold out the younger generation. In a way, this reminds me of the 50s and 60s Ampo and Zengakuren demonstrations held in Japan by the leftist student movement, and how the government eventually reigned them in by working with the dominant corporations and blacklisting those involved from eventual employment. And just as with the Zengakuren, there were martys for the cause. By blaming the youth, and their rebellious activities, the adult world can forgive itself and it's economic and social errors. Again, all these ideas are thinly veiled within an entertaining and character driven action film.

Saturday, March 24, 2007

Charisma カリスマ (Kurosawa Kiyoshi 黒沢清, 1999)

Charisma is easily described as "bizarre", and I believe it warrants such a claim more than many other films which are described as such. The storyline follows an ex-cop named Yakuibe (which translates as "grove" and "pond", and is played by Yakusho Koji) as he seeks redemption, or understanding, for why he seemingly caused the death of a hostage earlier in the film. Most of the plot is difficult, and maybe pointless, to describe but a good deal of it encircles a mysterious tree, named Charisma, which is guarded by a lunatic. Around it, is a forest that's being poisoned by either a deranged botanist or said mysterious tree. There's also a brigade of mercenaries attempting to steal Charisma. The botanist's sister is an out of place (within the film and the cast) and disenchanted young girl, who seems to be the only sexually charged being around. Charisma seems sophomorically thrown together, and even the director admits in an interview that he's not sure it all "works".

As odd as this all sounds, what really attracts is the visceral experience. The forest is framed in such a way that it seems endless. Earth and trees have never seemed so creepy in broad daylight, and, as one of the characters in the film remarks, it's a dangerous place. Shots of trees slowly dying, or humans eating mushrooms and slithering away in agony remain. The soundtrack is airtight, and never intrudes. The scenes are edited at a glacial pace, and you feel as alone and seperate from the world as the characters seem to. The plot of Charisma, and the environmental, psychological, or philosophical ideas that it attempts to dip into, are not the main attraction. That being said, they do intrude, and I've liked some of Kurosawa's other films a bit more (particularly Cure.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)