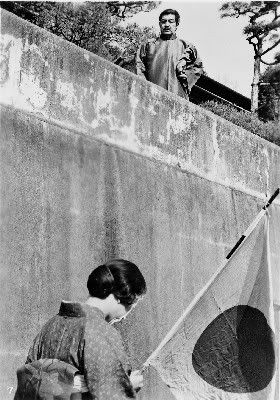

We begin with exposition as a lunatic asylum "mad scientist" ex-Nazi played by Amamoto Eisei discusses (he and his pals switch back and forth between menacing Japanese and scary German the whole film) how a massive diamond was lost and a young Japanese (Nakadai Tatsuya) has it in his possession- within his body, actually. A league of professional, and would-be, assassins make comedic attempts at Nakadai's life which are all thwarted, naturally, since even playing a little bit of a "dweeb", Nakadai is naturally graced with luck, charisma, wit, and a respectable fighting (or dodging) abilty. Turns out the diamond is a stolen Nazi item which was placed in Nakadai's body when he was eight. Nakadai is accompanied by a girl (Dan Reiko pictured above, fairly well known as Yuriko from Ozu's The End of Summer) and a goofy pal, who seems childishly eager for action.

Its telling that Okamoto's wildly hilarious, and sadly overlooked, film Age of Assassins (also known as The Epoch of Murder and Madness) shares its title, 殺人狂時代, with the Japanese translation of Charles Chaplin's blue beard Monsieur Verdoux. Both are the blackest of dry comedies, with a lack of sentimentality, light treatment of murder, and globe trotting anti-heroes making their way through piles of awkward situations and exotic, bizarre characters, both making oblique or vague swipes at politics. Chaplin plays for keeps more often than Nakadai, but Nakadai has a geeky coolness which seems to cross his dead stare from Teshigahara's Face of Another with the jaunty confidence of his character from Kill! that in some ways trumps Chaplin's foppish creepiness.

Though as much of a spoof of the spy film, with sultry femme fatales, gunplay, and strange gadgets, as a continuation of the "everyman" character Okamoto was so much a fan of, Age of Assassins manages to be fun and seemingly timeless, in a way few comedies can be. Watching this grasping even the smallest bit of dialogue is still entertaining after a handful of viewings. The same can be said of his other comedies that I've seen, including the sometimes maligned Oh, Bomb!, which is certainly among the most unique films of the 60s (something to be said for that, I believe.) It, like many dark comedies, defies categorization, and absolutely sets in stone what is commonly called the "Kihachi Spirit" in Japan, a sort of untouchable and undefinable quality Okamoto's films have, which is oh so modern.

The credits feature a DePatie-Freleng styled animated segment, which is probably the closest it comes to being dated. Concerning the visual style, Okamoto used the same cinematographer for this as Kill!, so it has a similar crisp detail, but it's a bit more high contrast (inspired by the black and white film noir underworld of assassins and spies, I suppose.) The score is almost inappropriately "emotional" at times, but enhances the odd factor. The action is believable, in a "chase film" sort of way, but the real greatness of Epoch of Murder and Madness is in the comedy. Not too broad (though Nakadai's small-enough-to-pedal-with-your-feet car, which emits burps and farts as it runs, runs counter to that claim) and like most of his films anti-authority and anti-war, a fair bit of cynicism and a love for the details of human nature seem to be the ideas behind it. A bit of his earlier The Elegant Mr. Everyman can be seen in the way Nakadai uses his voice as a blunt instrument of humor, streamlining dialogue in a way that almost sounds like narration. The cynical soldier, with aims at the ridiculousness of war, is then best exemplified in his Nikudan, or The Human Bullet, where Nakadai's Assassins character, Kikyo Shinji seems to be transposed into the Special Attack Forces. Properly enough, Nakadai narrated Human Bullet and the evil as hell Amamoto Eisei plays the main character's father (i.e. the villain). Worth noting that the "main character" of Human Bullet, played by Terada Minori, goes unnamed.

Someone needs to bring this, and the rest of Okamoto's comedic sixties work, to DVD badly. These films are so good (Oh, bomb!, The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman, and The Human Bullet), they must be seen to be believed.